British Gas risks fueling dirty war in killing fields of Honduras

On a death list: Bertha Oliva, head of the Committee of the Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras.Photo: Michael Gillard

On a death list: Bertha Oliva, head of the Committee of the Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared in Honduras.Photo: Michael Gillard

Death squads are operating in a coastal area where British Gas has started a multi-million pound offshore oil exploration drive. Michael Gillard reports from the killing fields of Honduras where peasant and community leaders are dying and a British company is at risk of fueling the dirty war.

Josbin Santamaria Caballero has disappeared. Soldiers came looking for him in the early hours of the morning on 30 October. They traveled in patrol boats through this remote but heavily militarized corner of northeast Honduras, where British Gas has just started exploring for oil that could lead to a £50m investment over the next ten years.

When the soldiers arrived, Josbin’s wife, Rosa, was making breakfast for their daughters Keilin, aged six, and two-year-old Nesly. She said the soldiers started beating her husband, a peasant farmer, and accusing him of being a sicario or assassin for local drug lords.

The long-abandoned region of Gracias a Dios has more than potentially large oil and gas fields. It is also a transhipment point for tons of cocaine sent by Colombian and Mexican cartels to the United States. However, there is little to thank God for among the farmers and fisherman living in this war zone.

Last year, a joint US-Honduran drugs operation led to the death of four innocent villagerstraveling home by small boat. Two were pregnant, one a teenager and the other a father. Four more were injured in a hail of bullets when the army helicopter gunship opened fire on the boat.

This October, when a helicopter landed at the Caballeros’ farm near Bruss Laguna, Rosa recalled in a witness statement how some 40 soldiers spread out to secure the area. “They blindfolded us so we couldn’t see the soldiers’ faces. I heard one, who appeared to be in charge, say ‘kill and burn him’, then two shots. When I was able to remove the blindfold I saw soldiers carrying Josbin onto the helicopter. I didn’t know if he was alive or dead. When the helicopter left they said to me, ‘We’ll give you five minutes to get out of here.’ I grabbed my two girls and fled to the mountains.”

Josbin’s mother Digna Santamaria with his two daughters

Josbin’s mother Digna Santamaria with his two daughtersRosa’s statement went to the Human Rights prosecutor. It arrived five days before the presidential elections on 24 November, which saw the return of the right wing National Party on an internal security and foreign investment manifesto.

An investigation is underway. However, there remains almost total impunity for human rights abuses committed by Honduran security forces. The prosecutor’s office is under-resourced and itself under threat from sicarios.

The US-trained army deny they were ever at the Caballero farm. The family has formally accused Colonel German Alfaro, commander of the Xatruch Task Force based near the border of Gracias a Dios, of planning Caballero’s murder. Days before his disappearance the colonel publicly denounced Caballero as an assassin. Last Wednesday he said: “This individual is a criminal and sicario. In fact, today someone came to my office willing to give evidence in a court that he had seen this man kill a 6-month old baby”. Col. Alfaro said Caballero also kills for the United Peasant Movement (MUCA) and fled to Gracias a Dios to escape justice.

Digna Santamaria, Caballero’s mother, is a high profile member of MUCA in Tocoa, the town where Col. Alfaro is based. Her two grandchildren are staying with Digna in the peasant settlement of La Confianza. She believes he was ‘disappeared’ because of her work in defending peasant land rights against landowners in the palm oil industry. Since 2010, 113 peasant leaders have been killed in the region.

Caballero’s case has been taken up by the Committee of the Relatives of the Detained and Disappeared (COFADEH) in Honduras. Bertha Oliva, its director, said the police and military are using the US-led war on drugs in Honduras to eliminate civilian political and community leaders seeking land reform in an area dominated by agribusiness, cocaine kingpins and now oil barons. Oliva has been marked for death many times since the early 1980s when her husband, a resistance fighter, disappeared. “The death squads are here waiting to strike at the people. I am on the list again,” she said.

Amnesty International has warned that human rights defenders, indigenous and peasant leaders, justice officials and journalists are subject to phone tapping, surveillance, death threats, kidnapping and murder. The military and private security working for big business are targeting and criminalising peasant communities, it said in a recent letter to presidential candidates.

British Gas is talking to the Honduran army and navy about future security arrangements in the coastal area of La Mosquitia in Gracias a Dios. It is concerned about working in the world’s most violent country and the third most corrupt in the Americas.

“We believe that Honduras offers considerable potential of reserves and felt that the offshore region had been largely overlooked by our competitors. We strongly support human rights within our areas of influence and recognise the significant impact that a major oil or gas discovery and development could make to the country,” said a spokesman for the company, which split in 1997 from the UK domestic gas supplier of the same name.

British Gas started negotiations with the Honduras government last year. In May it signed a contract securing rights to explore an offshore coastal area of 13,500 square miles. La Mosquitia is home to at least four indigenous peoples. In 1859, Honduras signed a treaty with the departing British Crown agreeing to hand back land titles to the ‘Mosquito Indians’.

The Honduran government only fully complied with the treaty this September when British Gas was consulting with Miskitu Asla Takanka, which the company says is “one of the largest groups representing indigenous communities”. However, Bertha Caceres, head of the Coordinating Council of Popular and Indigenous Organisations of Honduras, said the land title transfer is a way for the government to divide tribal peoples and buy off those opposed to or demanding greater investment from the oil and gas project. She said British Gas had not consulted her group.

Josbin Santamaria Caballero before he disappeared in October

British Gas is waiting for government environmental licences to begin surveys. The company has allocated £300,000 over the next two years for social and environmental investment projects.

A spokesman said: “We haven’t gone in with our eyes closed. Clearly the security situation and human rights issue is a major area of concern.”

Col. Alfaro denied there are any state-sponsored death squads operating in the northeast, except those linked to drug traffickers and the peasant movement. He said he would shortly be releasing recently received video and witness evidence proving that Caballero is alive.

It’s day 40 and his body is nowhere to be seen.

An edited version of this article first appeared in The Sunday Times on 8 December 2013. Photos: Michael Gillard ©

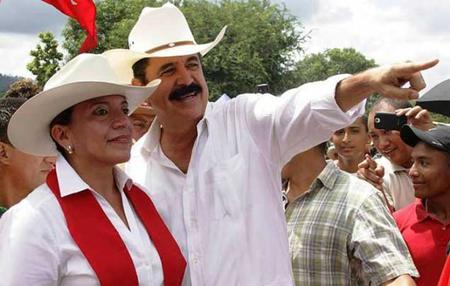

Xiomara Castro and Mel Zelaya. Credit: lr21.comAccording to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), Hernández won the presidency with 37% of the vote, well ahead of Castro at 29% and the Liberal Party candidate at 20%. (Honduran election law does not provide for a runoff if no candidate wins a majority.) But LIBRE, together with the libertarian Anti-Corruption Party (PAC) which received 14% of the vote, has refused to recognize the official results,

Xiomara Castro and Mel Zelaya. Credit: lr21.comAccording to the Supreme Electoral Tribunal (TSE), Hernández won the presidency with 37% of the vote, well ahead of Castro at 29% and the Liberal Party candidate at 20%. (Honduran election law does not provide for a runoff if no candidate wins a majority.) But LIBRE, together with the libertarian Anti-Corruption Party (PAC) which received 14% of the vote, has refused to recognize the official results,  Discount cards offered by National Party candidate Hernández. Credit: laprensa.hnMembers of our delegation saw the popular National Party

Discount cards offered by National Party candidate Hernández. Credit: laprensa.hnMembers of our delegation saw the popular National Party